Leisure Reflections No. 68: Clarification of Commitment vis-à-vis the six Qualities of Serious Leisure

news / June 6, 2025

By Robert A. Stebbins, University of Calgary

I wrote in Amateurs (Stebbins, 1979) the following seven paragraphs:

Up to this point, we have been working on a macro-sociological definition of amateurs: they are part of a professional-amateur-public system of functionally interdependent relationships. A social-psychological definition is also possible, and it is to this that we now turn.

Five attitudes are presented here, variations which separate amateurs from professionals and separate both from their publics (including dabbler and novices). These attitudes consist of: confidence, perseverence, continuance commitment, preparedness, and self-conception. Other attitudes, of course, have been discussed in the preceding pages; namely, dedication to and love for the field and identity with one’s colleagues. But amateurs and professionals are too much alike in these orientations for them to function as adequate differentiae. Confidence, on the other hand, is a prominent quality of experienced professionals, but absent in most amateurs (in sport see Weiss, 1969: 201-205). Questions dart through the typical amateur’s mind, such as: is this scientific finding significant? Is this the correct entry for my solo? what if I should fall while doing this dance step? I get so nervous in overtime that I cannot control the ball. The amateur, more than the seasoned professional, doubts his abilities, expresses them timidly, loses control through nervous tension, and the like. Professionals experience nervousness too but, as actress Katherine Cornell points out:

“You learn to control it better all the time” (in Funke and Booth, 1961: 200).

Perseverance similarly distinguishes these two groups. Any professional, seasoned or green, knows he must stick to his pursuit when the going gets tough (in the arts see Collingwood, 1958: 313-314). Assisting him here is the professional sub-culture. It helps him interpret vituperative comments from critics, coaches, conductors, directors, editors, and others, comments that the amateur is less likely to get, if he gets any at all. That subculture also encourages him to persist at shaping skills that seem to have reached a plateau in their development by pointing out that progress will resume in the future if certain steps are taken. Additionally, certain tricks of the trade that facilitate progress and that infrequently seep down to the amateurs, circulate among the professionals. One of these, found in certain professional sports, is how to foul an opposing player without detection by the officials, an ability that helps control him. Finally, injuries, especially a series of them, can be discouraging for any athlete, professional or amateur. Again, the former are aided, not only by continuous encouragement from colleagues, but also by medically trained personnel whose expertise in athletic injuries ensures the fastest possible recovery.

The greater perseverance of professionals is fostered, in part, by their greater continuance commitment. The concept of “continuance commitment,” developed by Becker (1960), Kantor (1969), and Stebbins (1970a, 1971a), is defined as “the awareness of the impossibility of choosing a different social identity … because of the imminence of penalties involved in making the switch” (Stebbins, 1971a: 35). Although continuance commitment to a professional identity is a self-enhancing matter – being forced to remain in a status to which one is attracted – penalties still accumulate to militate against its renunciation. For example, such movement is limited, for some professionals, by legal contracts, pension funds, and seniority. Others may have made expensive investments of time, energy, and money in obtaining training and equipment. With few exceptions amateurs never experience these sorts of pressures to stay at their pursuits. They have a “value commitment” but no continuance commitment (Stebbins, 1970a), while professionals have both. Professionals also evince a greater preparedness than amateurs. By “preparedness” is meant a readiness to perform the activity to the best of one’s ability at the appointed time and place. It refers to punctuality at such events as rehearsals and games and to arriving at these events in appropriate physical condition (not worn out from a day’s work or woozy from too many beers beforehand) with the required equipment in good repair and adjustment. Sir John Gielgud states the case for professional acting: ”the discipline of an actor is getting there every day a good hour before you go on, which I use n’t to do when I was young, but which I would not dream of not doing now — being ready” (in Funke and Booth, 1961: 21).

Amateur cellist Leonard Marsh (1972: 127) describes how he was unprepared to play in a chamber music concert:

I signified my readiness to play, and we started. It was only then that I found that, in my haste, I hadn’t put on my music glasses. My music glasses are carefully adjusted to read cello music at just the right distance. . .. I could manage fairly well by cocking my head at an awkward angle, but if I did it too much, it would look as if I were querying the interpretation of my companions… Toward the end of the movement I felt confident enough to take my eyes off the music and “look natural.” That was the mistake: I lost the vision of a whole line of music, and started playing the wrong notes.

Moving on to self-conception, it need only be mentioned that professionals and amateurs conceive of themselves in these terms. Just what the content of these conceptions are for each group in each field must be discovered through research. But self-identification as one or the other is perhaps the most reliable operational measure available at present for separating them.

These five attitudes comprise a social-psychological definition of amateur. The assumption should be avoided that professionals hold them in ideal form. This seldom happens. Even though they are significantly more confident, persevering, committed, and prepared than amateurs, they generally fall short of the highest points on these continua.

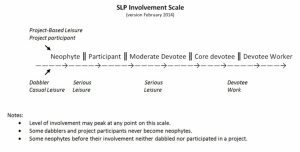

The Six Qualities

The serious pursuits are now further defined by six distinctive qualities (sometimes referred to as characteristics), qualities uniformly found among its amateurs, hobbyists, and volunteers (Stebbins 2007/2015, pp. 11–13). Sometimes this is a matter of degree. More precisely, their richest manifestation is found in these pursuits, with diluted manifestation or none at all evident in some casual and project-based activities. For example, even in the serious pursuits, neophytes are unlikely to put in the levels of effort and perseverance that moderate devotees do (see figure below). Today I see commitment as expressed in perseverance, effort, and career. This adds helpful precision to the broader concept of commitment.

Thus there is the occasional need to persevere. Participants who want to continue experiencing the same level of fulfillment in the activity must meet certain challenges from time to time. Another quality sharply distinguishing all the serious pursuits is the opportunity to follow a (leisure, or leisure-devotee work) career in the endeavor, a career shaped by its own special contingencies, turning points, and stages of achievement and involvement (the most extensive treatment now found in Stebbins 2014a). Moreover, most, if not all, careers here owe their existence to a third quality: serious leisure participants make significant personal effort using their specially acquired knowledge, training, or skill and, indeed at times, all three. Careers for serious leisure participants unfold along lines of their efforts to achieve, for instance, a high level of showmanship, athletic prowess, or scientific knowledge or to accumulate formative experiences in a volunteer role.

The serious pursuits are further distinguished by several durable benefits, or tangible, salutary outcomes such activity has for its participants. They include self-actualization, self-enrichment, self-expression, self-fulfillment, regeneration or renewal of self, feelings of accomplishment, enhancement of self-image, social interaction and sense of belonging, and lasting physical products of the activity (e.g., a painting, scientific paper, piece of furniture). A further benefit – self- gratification, or pure fun, which is by far the most evanescent benefit in this list – is also enjoyed by casual leisure participants.

Fifth, the possibility of realizing such benefits constitutes a powerful goal in the serious pursuits. Each serious pursuit is distinguished by a complex unique ethos that emerges in parallel with each expression of it. An ethos is the spirit of the community of serious leisure/devotee work participants, as manifested in shared context of attitudes, practices, values, beliefs, goals, and so on. The social world of the participants is the organizational milieu in which the associated ethos – at bottom a cultural formation – is expressed (as attitudes, beliefs, values) or realized (as practices, goals). The complexity of this ethos is also a matter of degree, which means that empirical and theoretical cut off points separating casual leisure and serious pursuits must be established statistically, using for example, the Serious Leisure Inventory and Measure (SLIM) or the 21-item scale of Tsaur and Liang (2008) (see later in this chapter).

According to David Unruh (1979, 1980) every social world has its characteristic groups, events, routines, practices, and organizations. It is held together, to an important degree, by semiformal, or mediated, communication. In other words, in the typical case, social worlds are neither heavily bureaucratized nor substantially organized through intense face-to-face interaction. Rather, communication is commonly mediated by newsletters, posted notices, telephone messages, mass mailings, radio and television announcements, and similar means.

Unruh (1980, p. 277) says of the social world that it:

must be seen as a unit of social organization which is diffuse and amorphous in character. Generally larger than groups or organizations, social worlds are not necessarily defined by formal boundaries, membership lists, or spatial territory…. A social world must be seen as an internally recognizable constellation of actors, organizations, events, and practices which have coalesced into a perceived sphere of interest and involvement for participants. Characteristically, a social world lacks a powerful centralized authority structure and is delimited by … effective communication and not territory nor formal group membership.

The social world is a diffuse, amorphous entity to be sure, but nevertheless one of great importance in the impersonal, segmented life of the modern urban community. Its importance is further amplified by the parallel element of the special ethos (which is missing from Unruh’s conception), namely that such worlds are also constituted of a substantial subculture. One function of this subculture is to interrelate the many components of this diffuse and amorphous entity. In other words, there is associated with each social world a set of special norms, values, beliefs, styles, moral principles, performance standards, and similar shared representations.

Every social world contains four types of members: strangers, tourists, regulars, and insiders (Unruh 1979, 1980). The strangers are intermediaries who normally participate little in the leisure/work activity itself, but who nonetheless do something important to make it possible, for example, by managing municipal parks (in amateur baseball), minting coins (in hobbyist coin collecting), and organizing the work of teachers’ aids (in career volunteering).

Tourists are temporary participants in a social world; they have come on the scene momentarily for entertainment, diversion, or profit. Most amateur and hobbyist activities have publics of some kind, which are, at bottom, constituted of tourists. The clients of many volunteers can be similarly classified. The regulars routinely participate in the social world; in serious leisure, they are the amateurs, hobbyists, and volunteers themselves. The insiders are those among them who show exceptional devotion to the social world they share, to maintaining it, to advancing it (see involvement scale in Stebbins 2014b, pp. 32–33 or in www.seriousleisure.net/Diagrams). Scott and McMahan (2017) describe in detail these exceptional participants who engage in “hard-core” leisure.

The sixth quality – participants in serious leisure tend to identify strongly with their chosen pursuits – springs from the presence of the other five distinctive qualities. In contrast, most casual leisure, although not usually humiliating or despicable, is nonetheless too fleeting, mundane, and commonplace to become the basis for a distinctive identity for most people. Some of the benefits (e.g., sense of belonging, self-gratification), aspects of a social world, and identity are also found in some casual leisure, albeit in comparatively watered-down form. In other words, notable perseverance and effort linked to a sharp sense of leisure career and durable benefits all of which are framed in the social world and ethos of the activity underlie the distinctive identity that emerges.

In short, commitment is and always has been a valid concept for serious leisure activities, though you can be more precise describing those activities as requiring perseverance and effort leading to a leisure career.

References

Becker, H.S. (1960). Notes on the concept of commitment. Amer. J. Soc. 66: 32-40.

Collingwood, R.G. (1958). The principles of art. New York: Oxford University Press

Funke, L. & J.E. Booth [eds.] (1961). Actors talk about acting. New York: Random House.

Kantor, R.M. (1968). Commitment and social organization. Amer. Soc. Rev. 33: 499-517.

s 48: 202-213.

Marsh, L. (1972). At home with music. Vancouver: Versatile Publishing Company.

Scott, D., & McMahan, K. K. (2017). Hard-core leisure: Conceptualizations. Leisure Sciences, 39(6), 569-574.

Stebbins, R.A. (1970a). On misunderstanding the concept of commitment. Social Forces 48: 526-529.

— (1970b). Career: the subjective approach. Socio/. Q. 11: 32-49.

— (1971a). Commitment to deviance. Westport, Conn.: Greenwood.

Stebbins, R.A. (2014a). Serious leisure: A perspective for our time. New Brunswick, NJ: AldineTransaction, Routledge, 2017.

Stebbins, R.A. (2014b). Careers in serious leisure: From dabbler to devotee in search of fulfillment. Houndmills, UK: Palgrave Macmillan.

Tsaur, S-H., & Liang, Y-W. (2008). Serious leisure and recreation specialization. Leisure Sciences, 30(4), 325-341.

Weiss, P. (1969). Sport: A philosophic inquiry. Carbondale: University of Southern Illinois Press.

Forthcoming:

Leisure Reflections Research Blog) No. 69, November 2025.

“What is leisure and what is not leisure: Some I pesky allied conceptions”